I say definitive not in a manner such that it's his best work, some would say Seven Samurai and others would say Yojimbo. This 1952 film of his is my personal favorite strictly because it is personal, as the introduction paragraph explains. That, and the beautifully constructed scenes as well as the insightful observation this film has on the theme of 'to live', which is what Ikiru means in Japanese. Watanabe, played by the great Takashi Shimura, is a bureaucrat who works at a public affairs office that deals with citizen complaints. He mainly sits at his desk and stamps pieces of papers, an infinite loop given the way his workplace is visualized. He has been doing this for thirty years and, as the narrator explains, he has been dead for thirty years. When he finds out, rather harshly, that he has stomach cancer and half a year to live, he starts to scramble and figure out what to do with his life.

Now, this plot to you may seem uninspiring. Yes, this narrative focus has been done and redone many many times to the point where one may consider it best to have cancer and then your life can be so much more risk-free...Anyways, Kurosawa takes this plot and constructs one hell of a study and illustration. This doesn't come close to the conventional Hollywood films we would see with this plot. Most of those films are about a life and one life only, usually using this individual to see life, in general, differently, be happy or at least content with the new image and then give a lasting catchphrase to make the audiences feel inspired. See, Ikiru is not just about a life, no, that's only half of it. It is about many lives and how they may interpret a life. Anachronistically, Kurosawa employs a meshing of both existential thought as well as structuralist thought in two halves of the film, though these philosophies were probably not in the mind of the director. We see Watanabe figure out how he can live his life through himself. Then, we see how other people interpret this individuality. In both instances, we view a kaleidoscopic realm of emotions and thought, except one stems from one person and the other stems from multiple people.

Kurosawa constructs scenes with such care and deliberate significance that each shot seems to be expressing some crucial aspect of living and thus we, as an audience, can only reflect this upon ourselves. One sequence involves Watanabe, who gets drunk as his first attempt to deal with his new direction in life, visits with an astray author a dance hall. It starts out as a medium, high-angled shot of Watanabe dancing with an unknown woman in a cramped crowd. The next shot then is a high-angled shot of the piano playing, which starts off the song everyone is mindlessly dancing to. The piano is in the foreground and we see how big the crowd is now as the frame is larger in relation to the dancinf people; Watanabe is nowhere to be found. Then, it cuts to a shot of men beating drums as the drums enter into the song. Again, a high-angled shot that peers over the drummers in the foreground and the large crowd above. Lastly, the sequence cuts to shots of the horn section as the stand up and play loudly. The composition, with its foundation as a high-angled shot, of course, has the horn players in the foreground, the drummers directly below them, then the piano, and finally what has become a sea of people dancing stiffly in the background. Though, I use the word background loosely in this case since Kurosawa employs this composition to have a flat look such that every element described within the frame looks as if they are all ontop of each pther, furthering the claustrophobic feel. Nevertheless, describing this sequence in words does not justify such beautiful execution of space, composition, sound, and thematic significance. Watanbe, in this portion of the film, has lost all sense of individuality much like he had in the public affairs office. Moreover, such immobility exhibited by the mechanical dancing restricts Watanabe of any active role, leaving him as passive as the crowd wants him to be.

This first half of the film, which includes the sequence discussed above, is Watanabe trying to understand what it means to live, having forgotten this after thirty years of nothing. He is mostly controlled by someone else, never motivated by his own will until the very last moments of this first half, where he realizes what he must do. Now, I will go ahead and spoil what happens next, because it is not really a twist yet the function of such a plot device is ingenious. Midway through the film Watanabe dies. We do not witness it. Instead, we witness his wake, where many men from his work sit around a serene picture of Watanabe, discussing the truth of his death and the significance of his role in creating a new park in a low-income neighborhood. This is really one long sequence, I think spanning around forty minutes, but it is one of the greatest scenes I have ever seen on film. Slowly, but surely, each man comes to their own realization of Watanabe, of course, as they get drunker. Yet, as I mentioned before, this kaleidoscopic construction of this scene is as honest as I have ever seen in a film about life. Kurosawa explains that a life is separated into what the individual feels and acts and what other people perceive these feelings and actions, yet it is the individual causality that brings life into an individual. Nonetheless, this is the most important dichotomy we think about everyday, just not as direct as this film shows it. Thus, this film takes on anything but a linear construction; this sort of scene would never be acceptable in Hollywood, mind you.

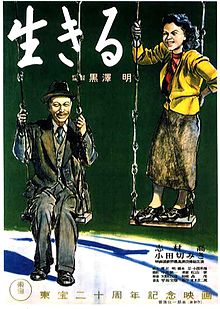

Ikiru is not a typical film about life, but it is far more truthful. Nothing is glamorized and ambiguity is everywhere. The lasting shot a viewer may have (the one that is on the side of this page now), of Watanabe gently swinging and singing in the snow, is supreme since it does not delve to closely into the character, but just enough for us to feel inspired. It is one of the most human films I have ever seen, and a film that, time after time, I feel strongly about and has made me reflect for days on end. I find encouraged with such storytelling, and Ikiru is one of the reasons I haven't folded under my own anxeity and become immobile.

No comments:

Post a Comment